Description

BIO :

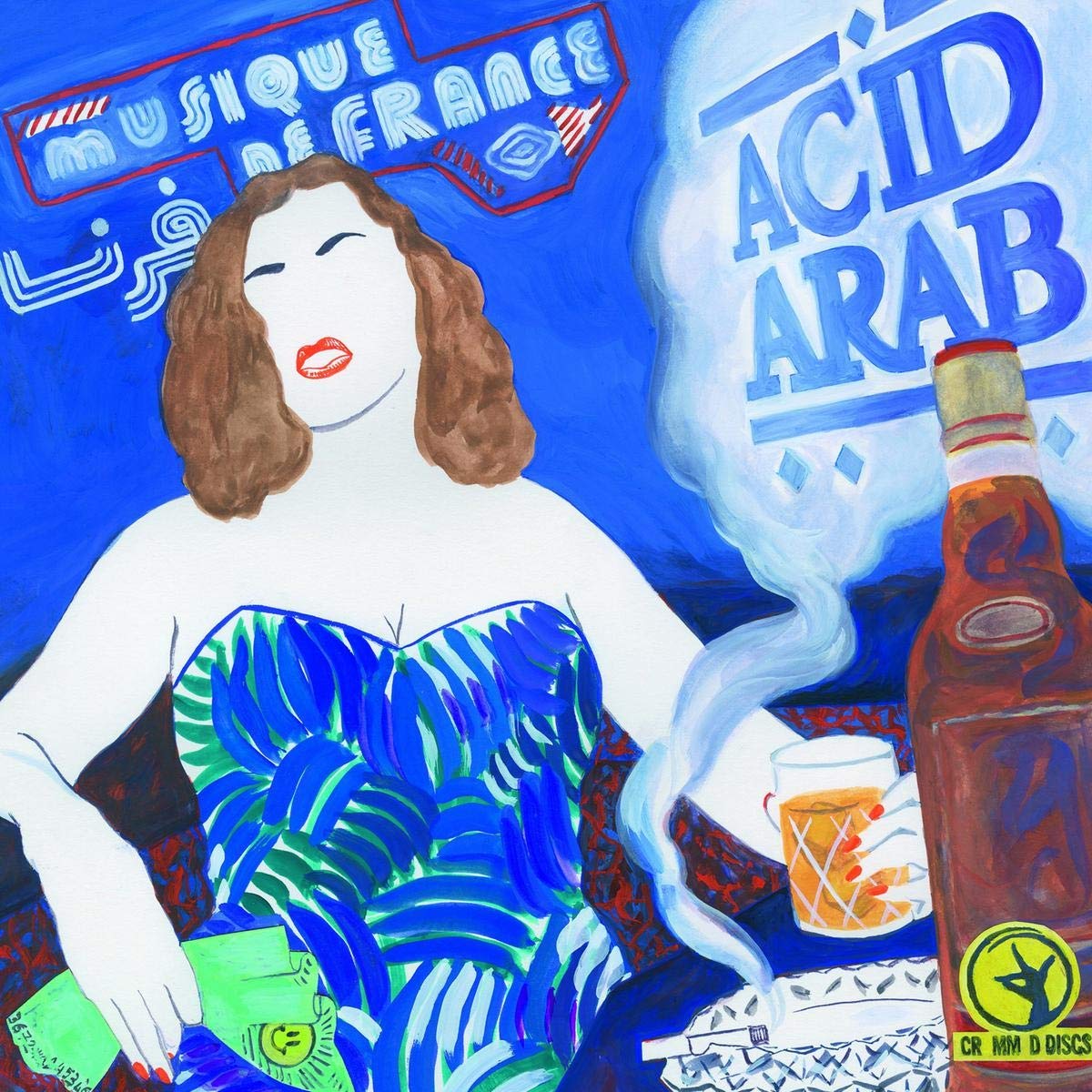

If « world music » was a marketing category devised in the ’80s to help sell records, it became the domain of the bourgeoisie, much like the worldbeat—which added electronic music into the mix—that followed it. That’s the legacy the Parisian duo of Guido Minisky and Hervé Carvalho, who operate as Acid Arab, have to contend with. As DJs, they’ve been hosting a party of the same name, which, in combination with a revelatory trip to Tunisia, led to two compilations on Versatile Records—the label of Gilb’R, the Tunisian DJ they visited the country with. Now they deliver Musique De France, Acid Arab’s debut album, and a mission statement of sorts. Using a moniker as fabulous as Acid Arab is automatically intriguing, and it raises certain expectations, which are more or less met by the music.

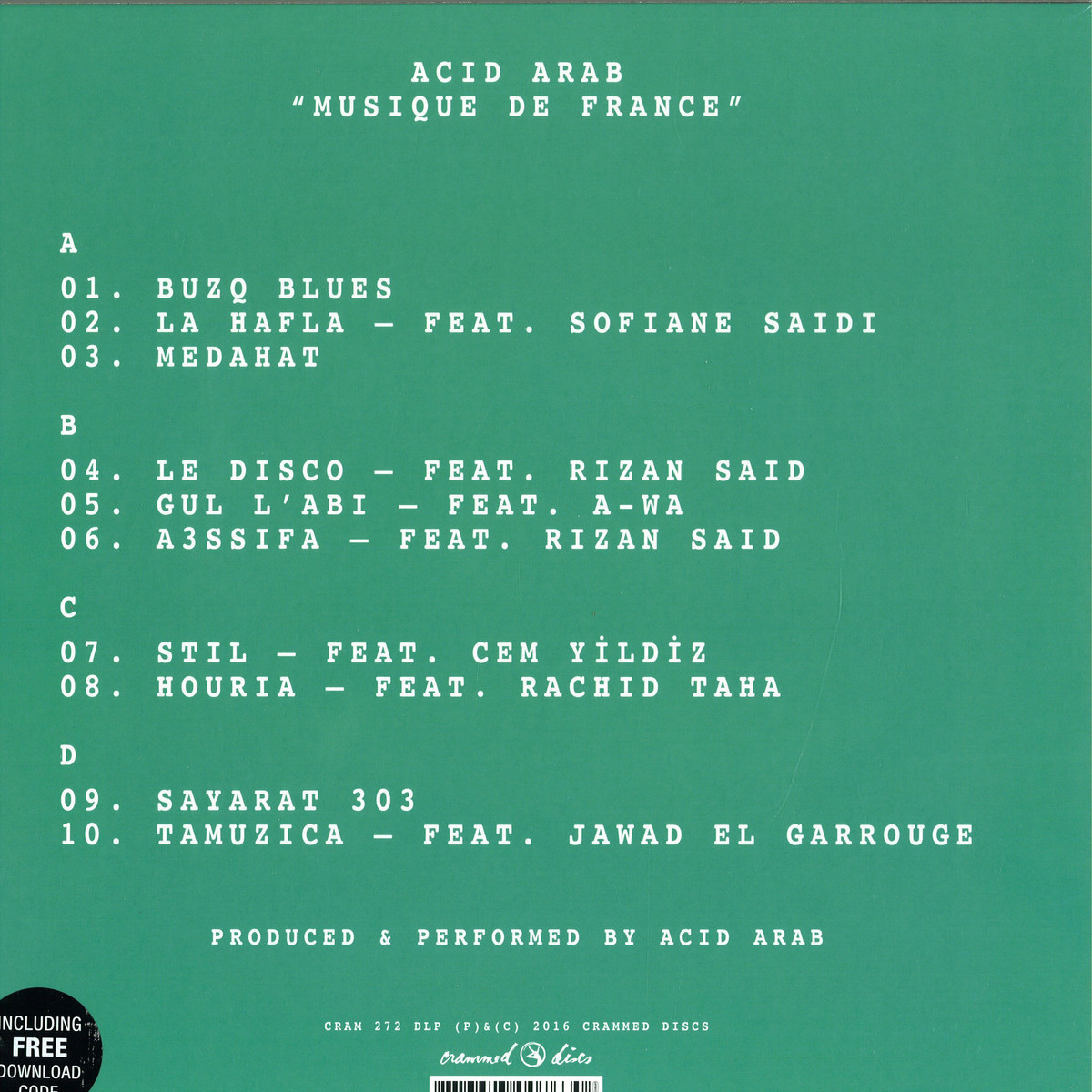

There are driving electronic beats and Middle Eastern or North African-derived modal melodies and instrumentation—or at least synths intended to emulate such instrumentation, such as rhaita horns—looped on almost every track. The beats and basslines are rooted in an underground sensibility that prevents the record from veering into blandly tasteful music. The Arabic elements help Musique De France feel special, presumably thanks to keyboardist Kenzi Bourras, who is also part of Algerian-French star Rachid Taha’s band. Seven of the ten tracks also feature collaborations, some of which form brilliant combinations, such as Taha’s evocative vocals in « Houria, » Yemenite singer AWA’s rousing call and response and quasi-yodeling in « Gul L’abi, » and Omar Souleyman keyboardist Rizan Said’s virtuosic playing on « Le Disco » and « A3ssifa. »

It’s interesting to hear Cem Yildiz’s droning saz and the multi-tracked vocals on « Stil, » or Algerian Sofiane Saidi’s plaintiveness on « La Hafla, » even though those stylistic contrasts don’t work as well. « Tamuzica, » featuring Jawad El Garrouge, feels the most gently traditional and the least « acid » of them all. As much as the desire for authenticity insists on tangible connections to the music, it also regularly translates into proof of a birthright. Minisky and Carvalho might argue that—thanks to imperialism, modern globalism and the resulting Arab community in Paris—that birthright also belongs to them. Given France’s colonial history, hinted at in the collaborators they enlist to help with the tracks, they would have a point.

But the real proof is in the music. You can hear the warmest affection for Acid Arab’s inspirations, like a desire to spread the joy they get from such artistry, and they seem to get that same respect from their collaborators. They draw from the immigrant communities to make a sound that, to them, is completely at home. Text by Lisa Blanning